Fifty years from now, some of you will be around and perhaps watching a show named “This Old Passive House”. What will be needed fifty years from now to fix up today’s high performance home to future standards?

Will today’s homes need more insulation? No.

Will today’s homes need better windows? No.

Will today’s homes need to be sealed better? No.

Will today’s homes need more ventilation? Yes!

Perhaps some of the products used in today’s high performance homes are not as durable as we had hoped and will need to be replaced, but in terms of increased energy efficiency, no further improvements will be needed. Today’s energy and material costs will be the same decades from now. Renewable energy cost is now lower than the cost of conventional energy sources, and renewable energy cost will continue to decrease. That is, our relative cost of energy in the future will not be higher than it is today, and that means the cost to make things, to go places, and to be comfortable will not be higher in the future.

A few decades from now, “This Old Passive House” will discuss how to increase the size of ventilation ducts because many of today’s high performance homes are being constructed with ductwork that is too small. Two reasons dictate that ventilation ducts are increased above those used with today’s ventilation standards. One reason is immediate. Today’s ventilation standards are too low and our health, cognition (brain health), sleep and productivity are being affected by poor indoor air quality. The second reason, increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide, is less immediate but like the progression of a steamroller, additional increases in building ventilation will be required in order to minimize carbon dioxide’s destructive effects on our brains. And, we need all the brain power we can muster to solve this problem for our children’s sake.

Today’s ventilation standards are not indoor air quality standards. They are standards based on odor, with the false hope that if something does not smell, air quality is ok [1]. Unfortunately, your nose cannot detect an unhealthy level of formaldehyde in a flooring material, countertop, or kitchen cabinet. In addition, recent research shows that carbon dioxide, until recently considered “benign” at current ventilation standards, significantly impacts several areas of brain performance (creativity, information processing decision making, etc) [2]. In fact, today’s nominal ventilation standard of 15 to 20 cubic feet per minute per person of fresh air needs to be doubled in order to reach a level of indoor air quality in which cognition is negligibly impacted.

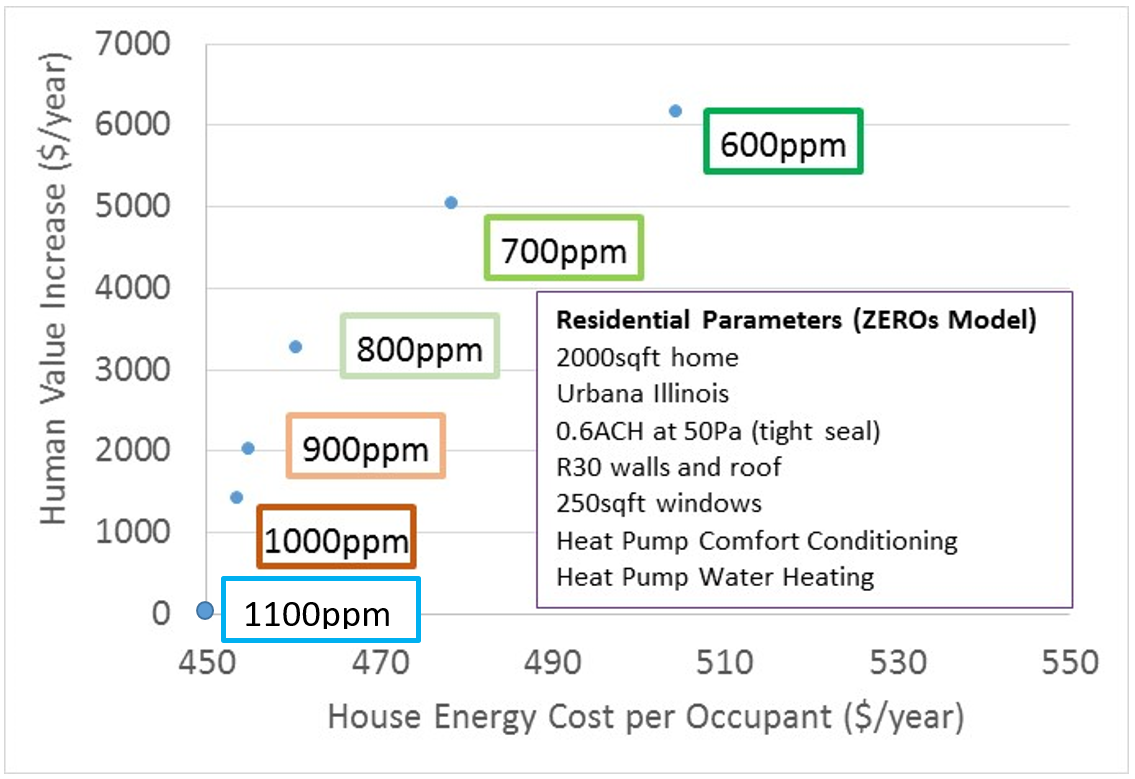

The cost to increase the air quality in a high performance home pales in comparison to the value of improved cognition productivity [3]. At a ventilation level of 20 cfm per occupant, with standard human activity and no other sources of carbon dioxide generation (no gas combustion, 100% electric home), the annual energy cost per occupant is $450 for a high performance, solar powered home. This level of ventilation results in an indoor air carbon dioxide concentration of 1100ppm which significantly degrades cognition performance in several areas.

Doubling ventilation rates to 40cfm per occupant lowers indoor carbon dioxide concentrations to 700 to 800ppm per occupant, with a significant improvement of cognition performance. The cost to double ventilation levels with a smart ventilation system is less than $50 per occupant with an associated human cognition productivity increase that is 100 times more valuable than the marginal energy cost increase (see Figure 1). High performance homes are not so sensitive to climate, and Figure 1’s trends are similar throughout the US.

Figure 1 Impact of increased ventilation on energy cost per occupant and human cognition productivity.

Figure 1 Impact of increased ventilation on energy cost per occupant and human cognition productivity.

The second reason for increased indoor ventilation is due to the ever increasing level of atmospheric carbon dioxide. Joe Romm, a physicists and a former Assistant Secretary in the Department of Energy, provides an excellent discussion of this topic. Carbon dioxide concentration was 300ppm when I was born, and has steadily risen to today’s 400ppm. With no uncertainty, atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations will reach a level within the next few decades that impairs our cognition capabilities. Further increases of indoor ventilation air flow will be required in order to minimize indoor cognition degradation in our homes and buildings because of ever increasing outdoor carbon dioxide concentrations.

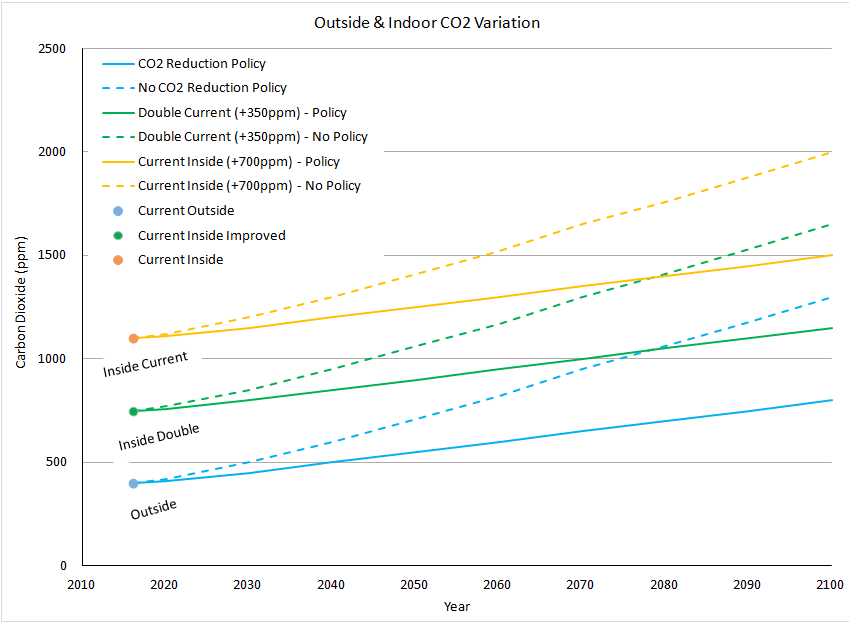

Figure 2 shows two predicted atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration increases. The two curves are from a computer model developed by University of Illinois researchers that predicts carbon dioxide concentration based on global carbon dioxide generation mitigation policies [4]. One curve shows a “no mitigation policy” curve and the other curve reflects trends for an “aggressive mitigation policy”. Two sets of curves also shown in Figure 2 show trends of indoor carbon dioxide concentration based on today’s fresh air ventilation standards, and indoor carbon dioxide concentration with an enhanced (doubled) fresh air ventilation standard. All curves start at today’s atmospheric condition, with atmospheric carbon dioxide at 400ppm, indoor carbon dioxide at today’s ventilation standard at 1100ppm, and increased (doubled) ventilation standard at 750ppm. As we progress toward a future with increasing carbon dioxide, we can view the trends in indoor carbon dioxide with the “no mitigation policy” and “aggressive mitigation policy” actions.

Figure 2 Atmospheric carbon dioxide and associated indoor carbon dioxide levels with current ventilation standards and improved (doubled) ventilation standards.

Figure 2 Atmospheric carbon dioxide and associated indoor carbon dioxide levels with current ventilation standards and improved (doubled) ventilation standards.

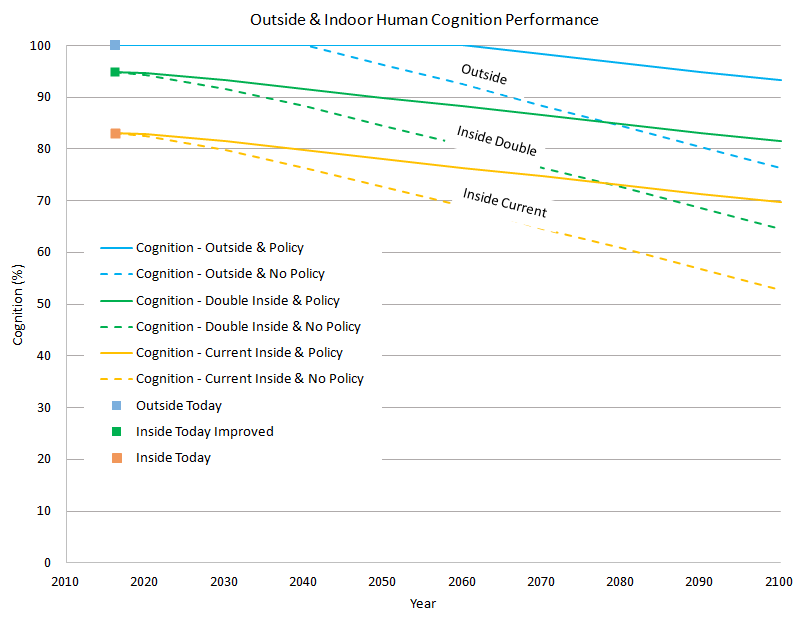

Figure 3 uses cognition performance research [2] coupled with atmospheric carbon dioxide predictions to show outdoor and indoor cognition performance trends in the future. Both “no mitigation policy” and “aggressive mitigation policy” paths will result in outdoor atmospheric carbon dioxide reaching a level that impairs cognition somewhere between 2040 and 2060. Today’s ventilation standards already diminish our indoor cognition performance by 15%, and 50 years from now when you’re watching “This Old Passive House”, indoor cognition impairment will be 25% to 30% with today’s ventilation levels. Doubling today’s ventilation levels will limit cognition decline to 15% to 20%. By 2066, we will need to again double our indoor ventilation standard in order to try and keep cognition impairment less than 10% in our buildings.

Figure 3 Decreased cognition performance due to carbon dioxide concentrations outside and inside buildings.

Figure 3 Decreased cognition performance due to carbon dioxide concentrations outside and inside buildings.

Doubling today’s ventilation, and doubling it again in the next few decades is real. Today’s homes with small diameter ducting that is sufficient for today’s insufficient ventilation will find that trying to double air flow will increase fan power by a factor of 8! Fan power is proportional to the air flow rate and the duct system pressure drop. Duct pressure drop increases with the square of the flow increase. Therefore, fan power increases with the cube of the flow increase, or, 23 = 8. When our not-too-distant tomorrow’s ventilation is quadrupled from today’s ventilation standards, fan power in today’s ductwork will increase by a factor of 64 (= 43)!

Today’s CERV smart ventilation systems are designed for higher ventilation rates because we look at the future as well as the present. Our concern and mission at Build Equinox is our health. Because the CERV automatically manages your home’s air quality, as increases in atmospheric carbon dioxide occurs, CERVs will increase to the ventilation level needed to keep homes healthy. As additional research results are published, we will continue reviewing and informing the CERV Community.

[1] Seichi Konzo; The Quiet Indoor Revolution; Small Homes Council-Building Research Council, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL 1992

[2] Joseph G. Allen, Piers MacNaughton, Usha Satish, Suresh Santanam, Jose Vallarino, and John D. Spengler; “Associations of Cognitive Function Scores with Carbon Dioxide, Ventilation, and Volatile Organic Compound Exposures in Office Workers: A Controlled Exposure Study of Green and Conventional Office Environments”;Env Health Perspectives; Oct 2015

[3] Piers MacNaughton, James Pegues, Usha Satish, Suresh Santanam, John Spengler, and Joseph Allen; “Economic, Environmental and Health Implications of Enhanced Ventilation in Office Buildings”; Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2015, 12, 14709-14722; doi:10.3390/ijerph121114709

[4] Clifford Singer, Leah Matchett, “Climate Action Gaming Experiment: Methods and Example Results”, Challenges 2015, 6, 202-228; doi:10.3390/challle6020202