Our pets need fresh air every bit as much as we do, and perhaps more. Being lower to the ground exposes pets and children to higher concentrations of dust and pollutants.

Pets are afflicted by many of the same environmental pressures that impact our health. Cancers and dementia are two health impacts affecting us and our dogs and cats. This American Veterinary Medical Association article discusses cancers in dogs. Because cancer in pets has not been extensively recorded, it is difficult to know if cancers are increasing or decreasing among our feline and canine family members. We do know that cancers in dogs are similar in extent to those in humans, and that the pollutant pressures that impact and inflame our bodies are doing the same to our pets.

On a pound for pound basis, pets require similar amounts of ventilation as humans. There is a persistent myth that pets generate much more carbon dioxide than humans. I attended a ventilation conference session a few years ago in which the salesperson presenter authoritatively stated that dogs produce 5 times more carbon dioxide than a human. Nonsense!

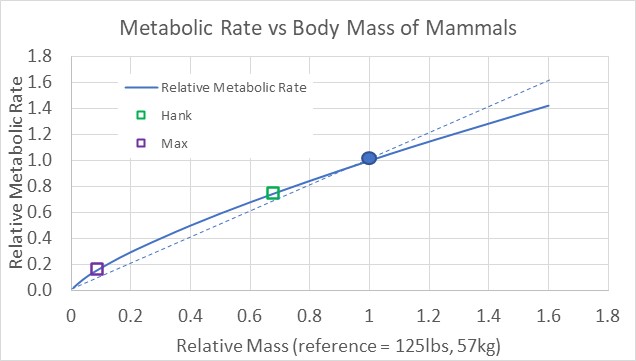

Metabolism and Body Mass Relation

Mammal ventilation requirements are directly related to an animal’s mass. If you would like to nerd out on this topic, read “Scaling of number, size, and metabolic rate of cells with body size in mammals”, by Savage, et al, published in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences), Vol 104, No 11, March 2007. It is an interesting article in which the authors examine the natural scaling of mammal metabolism to cell type and cellular metabolism. One of the curious features of our cellular makeup are two dominate cell types; cells that are relatively fixed in size, but vary in number as animal size varies, and cells that vary in size with animal size. Counting the amount of each type of cell in a mammal’s makeup results an overall estimation of that mammal’s metabolism.

The metabolism to body mass scaling has been applied to 626 mammal species over a six order of magnitude (1,000,000!) body mass variation range…think mice to elephants. The above plot of relative metabolism as a function of relative body mass shows how metabolism varies over a mass range typical of humans and our animal friends. The metabolism plot is based on a mammal reference weighing 125 pounds (57kg). The relation is not proportional, but deviates in a systematic manner. Mammals (and people) smaller than the reference generate 20 to 30% more carbon dioxide per body mass while mammals (and people) larger than the reference weight generate less carbon dioxide per body mass. For example, a 180 pound (84kg) adult exhales about 0.03kg per hour of carbon dioxide, or about 10% less than expected if metabolism and body weight were linearly related.

Hank “the Tank” is not pleased posing next to the CERV2 in his Ohio home. Hank’s hobbies include napping, counter-surfing, and howling at the moon. Hank’s nose is always working. One molecule of barbeque odor pulled into Hank’s nose triggers immense amounts of drool. At 85 pounds (39kg), Hank’s relative weight is 0.7 of the plot’s reference weight. His metabolism is about 10% greater per pound than the reference weight.

Max “the Wiener” is similarly not so pleased with his owner-imposed holiday outfit. Max weighs in at 11 pounds (5kg), for a relative weight of 0.09 of the reference weight. On a relative scale, Max produces 20% more carbon dioxide per body weight than the reference mammal.

If a household has multiple pets, simply add up the pet weights to determine what fraction of a human they add up to. For example, a wiener dog ranch with Max and 10 friends would add up to 125 pounds. The ventilation requirement for 11 wiener dogs is about 20% greater than that of a 125 pound person.

Odors

Pet odors are a separate concern from metabolism produced carbon dioxide. Some VOCs (volatile organic compounds) are released with exhaled breaths. Other VOCs are released through skin, flatulence, and burping. VOCs are also created as a result of microbe colonies residing on mammal bodies, producing various sorts of body odors.

VOC concentration and odor are two separate considerations. Some VOCs have relatively little odor at high concentration while other VOCs may be very odorous at low concentrations. The reactionary nature of VOCs produces chemical reactions among VOC compounds that sometimes form additional pollutants.

Alex (Build Equinox Co-Founder) Long’s four kitty and one dog household has lots of fur, but no odor according the housekeeper – she can detect odors in all of her pet-owning client homes except for their house. The CERV2 in Alex’ and Kate’s ‘s home is always moving air around the home, keeping odor concentration low, and reducing absorption and infusion of odorous compounds in house furnishings.

One of our early CERV owners told us that when he placed his home for sale, a prospective buyer told him that they have severe cat allergies and they could never live in a home that had cats. The prospective buyer was astonished when the homeowner informed them that two cats lived in the house. The homeowner told the prospective buyer about the CERV unit automatically managing the home’s air quality, which resulted in an immediate sale.

Summary

Our pets need fresh air every bit as much as we do for staying healthy and productive. Many of our pets catch colds, influenza, COVID, and other airborne transmitted diseases, as well as longer term diseases such as cancer and dementia that often have environmental bases.

Pet respiration results in fresh air ventilation needs that scale with the size of the pet. Large dogs exhale carbon dioxide at rates similar to a child of similar weight. Smaller mammals have slightly elevated (20 to 30%) carbon dioxide production rates